Most chest pain is not a sign of anything serious but you should get medical advice just in case. Get immediate medical help if you think you’re having a heart attack.

Immediate action required: Call 999 or 112 if you have sudden chest pain that:

- spreads to your arms, back, neck or jaw

- makes your chest feel tight or heavy

- started with shortness of breath, sweating and feeling or being sick

- lasts more than 15 minutes

You could be having a heart attack. You need immediate treatment in hospital.

Non-urgent advice:Talk to your GP if

you have chest pain that :

- comes and goes

- goes away quickly but you’re still worried

get medical advice to make sure it’s nothing serious.

Common causes of chest pain

In most cases, chest pain is not caused by a heart problem. Chest pain has many different causes.

Your symptoms might give you an idea of the cause. Do not self-diagnose. Talk to your GP if you’re worried.

| Chest pain symptoms | Possible cause |

|---|---|

| Starts after eating, bringing up food or bitter tasting fluids, feeling full and bloated | heartburn or indigestion |

| Starts after a chest injury or chest exercise, feels better when resting the muscle | chest sprain or strain |

| Triggered by worries or a stressful situation, heartbeat gets faster, sweating, dizziness | anxiety or panic attack |

| Gets worse when you breathe in and out, coughing up yellow or green mucus, high temperature | chest infection or pneumonia |

| Tingling feeling on skin, skin rash appears that turns into blisters | shingles |

Chest pain and heart problems

The most common heart problems that cause chest pain include:

- pericarditis – usually causes a sudden, sharp, stabbing pain that gets worse when you breathe deeply or lie down

- angina or a heart attack – they both have similar symptoms but a heart attack is life-threatening

You’re more likely to have heart problems if you’re older or at risk of coronary heart disease.

For example, if you:

- smoke

- are very overweight (obese)

- have high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol

- have a history of heart attacks or angina in family members under 60 years old

CHEST PAIN

Chest pain refers to pain felt anywhere in the chest area from the level of your shoulders to the bottom of your ribs. It is a common symptom. There are many causes of chest pain. This leaflet only deals with the most common. It can often be difficult to diagnose the exact cause of chest pain without carrying out some tests and investigations.

It is important to take chest pain seriously because it can sometimes indicate a serious underlying problem. Any new, severe, or persisting chest pain should be discussed with a doctor. This is particularly important if you are an adult and have a history of heart or lung disease. If the chest pain is particularly severe, especially if it is radiating to your arms or jaw, you feel sick, feel sweaty or become breathless, you should call 999/112/911 for an emergency ambulance. These can be symptoms of a heart attack.

Causes of chest pain

There are many possible causes of chest pain. Below is a brief overview of some of the more common causes.

Angina

Angina is a pain that comes from the heart. It is usually caused by narrowing of the coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart muscle.

In the early stages, blood supply may be adequate when you are resting. However, when you exercise, your heart muscle needs more blood and oxygen, and if the blood cannot get past the narrowed coronary arteries, your heart responds with pain.

The chest pain caused by angina may feel like an ache, discomfort or tightness across the front of your chest.

Angina pain can also occur with coronary artery spasm or cardiac syndrome X.

Heart attack

During a heart attack (myocardial infarction), a coronary artery or one of its smaller branches is suddenly blocked. This cuts off the blood supply to part of the heart muscle completely.

The most common symptom of a heart attack is severe chest pain at rest. Unless the blockage is quickly removed, this part of the heart muscle is at risk of dying. To find out more about the symptoms and treatments for a heart attack.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

This is a general term which describes a range of situations including acid reflux and oesophagitis (inflammation of the lining of the oesophagus, or gullet).

Heartburn – usually a burning in the lower chest and upper abdomen – is the main symptom of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Severe chest pain can develop in some cases and can be mistaken for a heart attack. To find out more about the symptoms and treatments.

Costochondritis

The rib cage is a bony structure that protects the lungs. Softer, more flexible cartilage attaches the ribs to the breastbone (sternum) and the sternum to the collar bones (clavicles) at joints. In costochondritis, there is inflammation in one or more of these joints.

Costochondritis causes chest pain, felt at the front of the chest. This is typically a sharp, stabbing chest pain and is worse with movement, exertion and deep breathing.

Strained chest wall muscle

There are various muscles that run around and between the ribs to help the rib cage to move during breathing. These muscles can sometimes be strained and can lead to chest pain in that area. If a muscle is strained, there has been stretching or tearing of muscle fibres, often because the muscle has been stretched beyond its limits. For example, a strained chest wall muscle may sometimes develop after heavy lifting, stretching, sudden movement or lengthy (prolonged) coughing. The chest pain is usually worse on movement and on breathing in.

Anxiety

Anxiety is quite a common cause of chest pain. In some people, the chest pain can be so severe that it is mistaken for angina. Chest pain due to anxiety is known as Da Costa’s syndrome. Da Costa’s syndrome may be more common in people who have recently had relatives or friends diagnosed with heart problems, or in people who themselves have recently had a heart attack. Investigations show that the coronary arteries are normal with no narrowing.

What’s causing your chest pain?

Chest pain is common but, understandably, it can be a source of anxiety.

Less common causes of chest pain

Some of the less common causes of chest pain include the following.

Pleurisy

Pleurisy is due to inflammation of the pleura, a thin membrane with two layers – one which lines the inside of the muscle and ribs of the chest wall, the other which surrounds the lungs. It can cause a ‘pleuritic’ chest pain. This is a sharp, stabbing chest pain, typically made worse by breathing in or by coughing.

Less common but more serious causes of pleuritic pain include pneumonia, or a blood clot in the lung (pulmonary embolism) or a collapsed lung.

Pulmonary embolism (PE)

A PE occurs when there is a blockage in one of the artery blood vessels in the lungs – usually due to a blood clot (thrombus) which formed in another part of the circulation. A PE usually causes sharp chest pain felt when breathing in (pleuritic chest pain). Other symptoms include coughing up blood (haemoptysis), mild fever and rapid heart rate.

Pneumothorax

A pneumothorax is air that is trapped between a lung and the chest wall. The air gets there either from the lungs or, following chest wall injury, from outside the body.

A pneumothorax typically causes sudden, sharp, stabbing chest pain on one side. The pain is usually made worse by breathing in and you can become breathless. Usually, the larger the pneumothorax, the more breathless you become.

Peptic ulcer

A peptic ulcer is an ulcer on the inside lining of the upper gut caused by stomach acid.

Shingles

Shingles is an infection of a nerve and the area of skin supplied by the nerve. It is caused by the same virus that causes chickenpox. Anyone who has had chickenpox in the past may develop shingles.

The usual symptoms are pain and a rash over the strip of skin supplied by one nerve, sometimes on the chest wall. The pain often starts before the rash appears.

Is my chest pain serious?

Seek medical help immediately if you have chest pain that is in the middle of your chest, is crushing or squeezing and comes with any of the following symptoms:

- Pain that spreads to the neck, jaw, or one or both shoulders or arms.

- Sweating.

- Shortness of breath.

- Feeling sick (nausea) or being sick (vomiting).

- Dizziness or light-headedness.

- Fast or irregular pulse.

You should call 999/112/911 for an emergency ambulance.

There are many different causes of chest pain. Some are more serious than others. Any new, severe, or persisting chest pain should be discussed with your doctor. This is particularly important if you are an adult and have a history of heart or lung disease.

What investigations may be advised?

Your doctor will usually ask you some questions to try to determine the cause of your chest pain. He or she may also examine you. Based on what they find, he or she may advise you to have some investigations, depending on what cause for your chest pain they suspect. Investigations for chest pain can include:

A ‘heart tracing’

There are usually typical changes to the normal pattern of the ‘heart tracing’ (electrocardiogram, or ECG) in a heart attack.

Blood tests

A blood test that measures a chemical called troponin is the usual test that confirms a heart attack. Damage to heart muscle cells releases troponin into the bloodstream. Another blood test that may be suggested is a D-dimer test. This detects fragments of breakdown products of a blood clot. A positive D-dimer test may raise the suspicion of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or a PE.

Chest X-ray

A chest X-ray can look for pneumonia, collapsed lung (pneumothorax) and other chest conditions.

Other scans and imaging

- Myocardial perfusion scan – often done to confirm the diagnosis of heart chest pain (angina).

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging – also to confirm heart chest pain, this is a type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

- CT coronary angiogram – a quicker alternative to an MRI scan, in which a CT scan is used to to look in detail at your coronary arteries.

- Coronary angiography – this test uses specialist X-ray equipment and dye injected into the coronary arteries to show the location and severity of any narrowing of the arteries.

- Isotope scan and CTPA scan look at the circulation in the lung. CTPA stands for ‘computerised tomography pulmonary angiogram’. They can show quite accurately whether or not a PE is present.

- Endoscopy – which uses a thin, flexible telescope passed down your gullet (oesophagus) to examine your stomach lining. This may be recommended if your team thinks your chest pain could be caused by gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or a peptic ulcer.

What may be advised to help manage the problem?

This will depend on the cause that is found for your chest pain.

MANAGEMENT OF CHEST PAIN

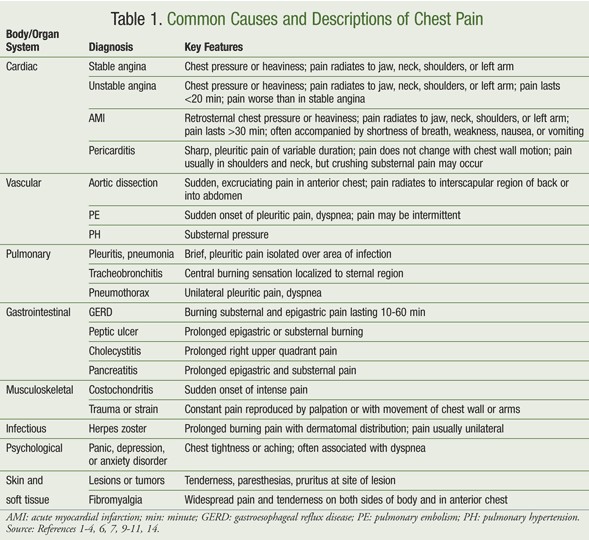

Common causes of chest pain and their descriptions are listed in TABLE 1. The goal of chest pain management, as with all pain control, is to find the cause and treat it appropriately, with the right medication at the lowest effective dose with the fewest possible side effects. The general principles of respiratory, cardiac, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal (GI), and psychological disorders apply to the treatment of both cardiac and noncardiac chest pain.

Cardiac Chest Pain

Several life-threatening causes of chest pain require immediate attention and must be ruled out before other causes can be determined. These conditions include acute coronary syndrome (ACS), pulmonary embolism (PE), and aortic dissection. ACS is the most significant potentially fatal diagnosis of chest pain. Fifteen percent to 25% of patients who present with chest pain are diagnosed with ACS, a broad diagnosis that includes any condition that results in myocardial ischemia, ranging from unstable angina to acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Myocardial ischemia usually occurs in the presence of coronary atherosclerosis, but ischemia may accompany any disease or process that occludes a coronary artery or decreases myocardial perfusion, such as a thrombus or embolism, aortic stenosis, or cardiomyopathy.

Angina, the classic manifestation of myocardial ischemia, is usually described as heavy chest pressure or a squeezing or burning sensation and is often accompanied by difficulty breathing. Angina often radiates to the left shoulder, neck, or arm and builds in intensity over a period of several minutes. While exercise or psychological stress can trigger angina, the condition most commonly occurs without obvious precipitating factors. The typical presentation includes pain that is substernal, provoked by exertion, and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin. Anginal chest pain indicates a high risk of CAD.

An atypical presentation of chest pain lessens the likelihood that the chest pain is due to ischemia. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines list several descriptors that are not characteristic of myocardial ischemia: pleuritic pain (sharp pain caused by respiratory movements or cough); pain or discomfort located primarily in the middle or lower abdomen; pain localized to the tip of one finger; pain reproduced with movement or by palpation of the chest wall or arms; constant pain persisting for many hours; brief pain lasting a few seconds; and pain that radiates to the lower extremities. However, atypical symptoms cannot rule out the presence of ACS and should be only one consideration in the diagnosis of chest pain.

Oxygen supplementation is routine for all patients with chest pain related to ACS. It is recommended for all AMI patients during the first 6 hours after symptom onset, and longer if other disease states causing hypoxemia are present.9 Also, in patients presenting with chest pain consistent with ACS, aspirin should be administered as soon as possible and continued indefinitely if no aspirin allergy exists. Clopidogrel should be substituted in the case of an aspirin allergy or GI intolerance.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors block platelet aggregation and are recommended for patients with unstable angina and non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Currently available agents include abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide. Additionally, the ACC/AHA guidelines recommend anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) added to antiplatelet therapy for the treatment of ACS. Currently available LMWHs include enoxaparin, dalteparin, and tinzaparin. UFH should be adjusted to maintain a partial thromboplastin time of 1.5 to 2.0 times control. LMWH is an alternative to UFH in patients younger than 75 years with stable renal function; LMWH is preferred over heparin as an anticoagulant in the absence of renal failure.

Nitroglycerin, the cornerstone of antianginal treatment, provides symptom relief in patients with ongoing cardiac chest pain. Morphine may also be used to control pain in AMI patients, but should be administered cautiously at low doses. Also, IV or oral beta-blockers should be given to AMI patients without a contraindication to such treatment, such as ST-elevation myocardial infarction and moderate left ventricular failure, or bradycardia, hypotension, shock, active asthma, or reactive-airway disease.

Acute aortic dissection is the most common and most lethal aortic emergency, and it has the highest mortality rate among life-threatening causes of chest pain.9 Acute aortic dissection causes the sudden onset of excruciating, ripping pain whose location reflects the site and progression of dissection. Aortic dissection may also present with stroke, heart failure, syncope, lower-extremity pain or weakness, back and flank pain, and abdominal pain.

Aortic dissection usually occurs in the presence of risk factors such as hypertension, pregnancy, atherosclerosis, illegal drug use, connective-tissue disease, and conditions that lead to the degeneration of aortic tissue. Aortic dissection is treated by eliminating factors that are favorable to the progression of dissection, including elevated blood pressure. Appropriate interventions include sodium nitroprusside administered IV to achieve a systolic blood pressure between 100 and 120 mmHg, and oral or IV beta-blockers to avoid reflex tachycardia secondary to sodium nitroprusside. Prompt surgical consultation is recommended for patients with suspected aortic dissection.

The annual incidence of PE is estimated to be 200 cases per million people. The mortality rate for untreated PE is 18.4%, accounting for up to 200,000 deaths annually in the U.S. PE often causes dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain, but PE may be asymptomatic. Larger emboli cause severe and persistent substernal pain, whereas smaller emboli cause lateral pleuritic chest pain. Anticoagulant therapy with UFH, LMWH, or fondaparinux effectively reduces mortality in PE.

Noncardiac Chest Pain

Noncardiac chest pain may be caused by musculoskeletal disorders, abnormalities of the abdominal viscera, and psychological conditions, among other anomalies. Even more than cardiac chest pain, noncardiac chest pain is difficult to define, diagnose, and manage.

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with chest pain are classified as having noncardiac chest pain based on normal findings of cardiac catheterization or other diagnostic evaluations. Each year, approximately 200,000 new cases of noncardiac chest pain occur in the U.S. Morbidity among noncardiac chest pain patients is considerable, and these patients tend to have a high use of health care services and empiric therapies and report a general dissatisfaction with care received.

Respiratory and pleuropulmonary disorders are common causes of noncardiac chest pain. Pleuritis and pleural effusions occur frequently in connective-tissue diseases, and the pain is often relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); corticosteroids may reduce inflammation in patients who remain symptomatic after NSAID treatment. Pneumonia frequently presents with chest pain localized over the area of infection. Pneumonia treatment is based on antimicrobial therapy guided by local surveillance reports.

GI disorders are a common source of noncardiac chest pain. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), one of the most common causes of noncardiac chest pain, presents with pain resembling angina. GERD may be associated with a squeezing or burning type of substernal pain that radiates to the neck, back, or arms. The pain is generally worse after meals and in the supine position, and exercise and emotional stress can precipitate GERD-associated pain. GERD has been reported in as many as 60% of people with chest pain.

Chest pain associated with GERD is manageable, most often with a proton pump inhibitor. Additionally, weight loss is recommended for overweight or obese patients with GERD and noncardiac chest pain. Other lifestyle modifications, including avoiding trigger foods and raising the head of the bed, may not completely relieve chest pain associated with GERD.

Psychological factors are significant in the diagnosis and management of chest pain. Approximately 30% of patients with noncardiac chest pain experience panic or anxiety disorders. There is a high rate of anxiety and depression among patients with cardiac and noncardiac chest pain, so the pain should not be immediately attributed to psychological factors before organic etiologies are ruled out. Treatment of psychogenic causes of chest pain is not specific to chest pain and includes cognitive behavioral therapy and anxiolytic and antidepressant therapy.

Musculoskeletal conditions are the cause in 25% to 35% of patients with noncardiac chest pain. Chest pain reproducible by palpation is most likely musculoskeletal in origin. One common cause of noncardiac chest pain is costochondritis, the inflammation of a rib or cartilage attached to a rib. This condition is relieved by analgesics, local anesthetics, or anti-inflammatory agents. Infectious diseases such as herpes zoster may also cause diffuse chest pain. The pain usually resolves once the infection is adequately treated with antiviral agents.

Treatment

With a broad differential diagnosis, a definitive cause is not always established for chest pain, and continued evaluation is often the best course. In the absence of a definitive diagnosis, systemic analgesia for chest pain is appropriate. First-line analgesics, including acetaminophen and NSAIDs, may be used safely for mild pain in most patients. Opioids and adjuvant analgesics may be added if first-line therapy does not relieve the pain. Doses of analgesic agents should be adjusted individually based on level of pain, medication history, and allergies.

Appropriate evaluation and management of chest pain, whether its origin is cardiac or noncardiac, involves treating the underlying cause of the pain while improving patient outcomes and minimizing drug interactions and adverse events. For patients in the acute care setting, chest pain may occur as part of the symptoms or sequelae that require attention and pharmacologic management.

References

- HSE

- Patient Info

- 1. Lee-Chiong T, Gebhart GF, Matthay RA. Chest pain. In: Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin T, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010.

2. Brown JE, Hamilton GC. Chest pain. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2009.

3. Jones ID, Slovis CM. Pitfalls in evaluating the low-risk chest pain patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am.

4. Cayley WE Jr. Diagnosing the cause of chest pain. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2012-2021.

5. Karnath B, Holden MD, Hussain N. Chest pain: differentiating cardiac from noncardiac causes. Hosp Physician. 2004;40:24-27,38.

6. Cannon CP, Lee TH. Approach to the patient with chest pain. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, eds. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

7. Yelland M, Cayley WE Jr, Vach W. An algorithm for the diagnosis and management of chest pain in primary care. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:349-374.

8. DiPiro JP, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008.

9. Haro LH, Decker WW, Boie ET, Wright RS. Initial approach to the patient who has chest pain. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:1-17,v.

10. Brims FJ, Davies HE, Lee YC. Respiratory chest pain: diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin North Am.

11. Woo KM, Schneider JI. High-risk chief complaints I: chest pain—the big three. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:685-712,x.

12. Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction—2002: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). Circulation.

13. Ruigómez A, Massó-González EL, Johansson S, et al. Chest pain without established ischaemic heart disease in primary care patients: associated comorbidities and mortality. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e78-e86.

14. Oranu AC, Vaezi MF. Noncardiac chest pain: gastroesophageal reflux disease. Med Clin North Am.

15. Eken C, Oktay C, Bacanli A, et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders in patients presenting with chest pain to the emergency department: a comparison between cardiac and non-cardiac origin. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:144-150. - USPharmacist