By Kathleen McGrory, Neil Bedi

Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital broke Florida law by failing to tell regulators about two serious medical errors, according to a state report.

The report, released Tuesday by the Agency for Health Care Administration, contradicts statements by the hospital last month that it notified the “right regulatory agencies” when mistakes were made by its heart-surgery unit.

AHCA also cited the hospital for failing to tell the parents of one patient about an object left in their child after surgery. State law requires hospitals to inform either the patient or the patient’s representative.

AHCA inspectors visited All Children’s last month, after a Tampa Bay Times article detailed problems within the hospital’s Heart Institute. Among them: an increase in the mortality rate among heart surgery patients, and two instances in which surgical needles had been left in children.

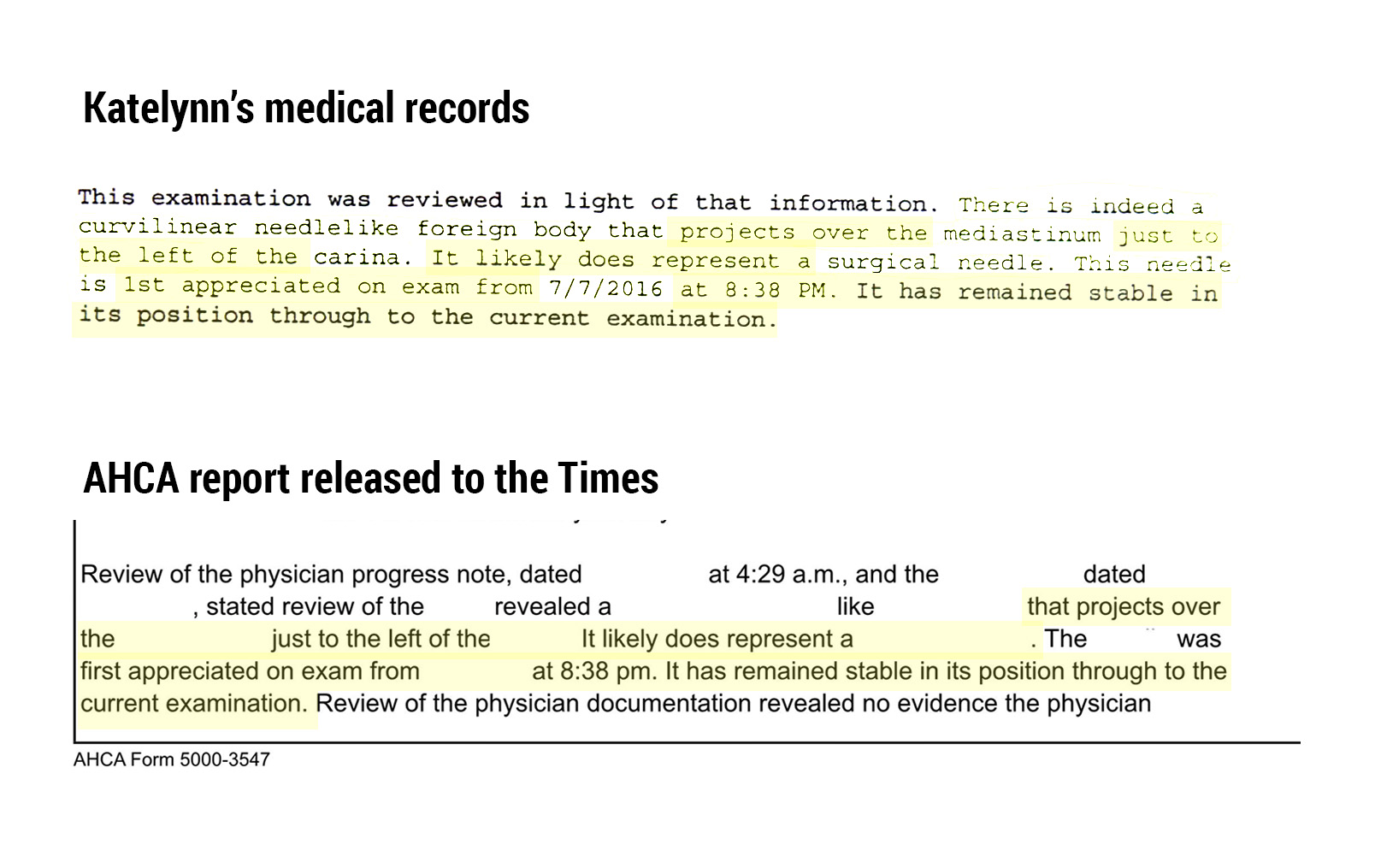

In one of the cases, the needle remained in the child’s aorta. The girl’s parents told the Times they did not find out until a follow-up visit at a doctor’s office, and when they returned to the hospital, the surgeon said it didn’t exist.

The AHCA report appears to confirm that the parents were not originally told about the needle. Although the copy released to the Times was redacted to remove identifying information, including the object left inside the patient, other details match the girl’s medical records, including the hour and minute of events, specific quotes from doctors’ reports and the parents’ description of returning to the hospital’s emergency room after learning a needle had been left in their child. “The parents had not previously been told,” the report said.

“The physician documentation revealed no evidence the physician informed the patient’s guardians,” it said.

The hospital issued a statement Tuesday saying it would comply with AHCA’s findings “without hesitation.”

“We may also seek clarification so that we are absolute in our compliance for appropriate reporting,” the statement said. “We want to stress to our community that we have been modifying, updating and improving our processes during the two years since these events and we feel confident that these measures will ensure better care and better communications for our patients and families.”

Last month, the hospital’s CEO, Dr. Jonathan Ellen, told the Times that the Heart Institute had experienced a string of “challenges.” But, responding to questions about the needle incident, he said: “If we found something that went wrong, we would notify our board, we would notify the right regulatory agencies, we would look at our processes.”

The hospital later said that leaving a needle smaller than 10 millimeters is allowed under its policies if “the time that the surgeon spends looking for a small needle may cause harm.” Under those circumstances, the hospital did not believe it was required to report to AHCA, it said at the time.

In an interview, Alan Levine, who served as AHCA’s chief administrator from 2004 to 2006, called failing to report an adverse incident to the state a “very serious breach of confidence.”

AHCA’s oversight depends on hospitals and other health care facilities accurately reporting errors, he said. It’s how the state finds and tracks problems and ensures they don’t happen again.

The agency did not announce any fines or actions related to the deficiencies, though hospitals generally are given a chance to contest the citations.

Medical experts say such events should always be disclosed to the patient. All Children’s has said its policy is to always notify parents about problems.

The Heart Institute has drawn increased scrutiny in recent weeks.

Ellen did not elaborate on its challenges in the April interview with the Times, and declined to release the latest performance outcomes. But he said the hospital was doing fewer heart surgeries and referring some complicated cases elsewhere. He also said one of the hospital’s three heart surgeons — who medical records identify as the surgeon in the needle case — remained on staff but was no longer actively operating.

The surgeon, Dr. Tom Karl, declined comment through a hospital spokeswoman Tuesday and did not respond to an email from the Times.

The needle incident occured in 2016. The patient’s parents, Amara Le and Joshua Whipple, said it was later removed during an unrelated procedure at a different hospital. They settled with All Children’s out of court for a total of about $50,000, most of which their daughter, Katelynn, will receive as an adult, records show.

Le declined to comment on Tuesday.

State regulators began reviewing the incident on April 26, six days after the Times story published online.

Before the report was finished, the Heart Institute’s problems were already being discussed by AHCA’s Pediatric Cardiology Technical Advisory Panel. The committee of cardiologists and cardiac surgeons is working to develop standards for pediatric cardiac surgery programs across Florida.

During a May 3 conference call, one of the members, Dr. Jorge McCormack, said he was “really worried” that All Children’s had chosen not to disclose its 2017 surgical outcomes to the public in light of the Times’ findings.

Other members of the panel cautioned that one year of data would not fully represent the program. Like many other heart surgery units across the country, All Children’s publishes four-year averages.

McCormack declined to comment to the Times.

The Joint Commission, a national hospital accreditation group that sets standards for safe patient care, also said All Children’s did not inform it about at least one of the needle incidents. Reporting to the organization is optional, but encouraged.

The Joint Commission has requested a written response from All Children’s regarding the incident, a spokeswoman said.